A quick tour of hyperinflation and the

possible consequences for America

"No one can predict the future," I heard a voice say as I walked into the offices of Backwoods Home Magazine. The speaker went on to add, "But there are a lot of reasons to believe we are in danger of entering a period of hyperinflation of the dollar."

I hesitated because I knew the voice and I followed it to Dave Duffy's office. Dave's the guy who publishes this magazine. But the speaker I was hearing was none other than our poker-playing friend from Southern California, O.E. MacDougal.

I walked into Dave's office and there was the pair of them, Dave and Mac, drinking wine and talking. After greeting me, their conversation seemed to drift to the subject of the steelhead that were making their way up the Rogue River just north of town. But I wanted them to get back to what I'd heard them discussing when I first came in. So I cut in.

"Hey, I heard you saying something about hyperinflation. I know I've seen references to it on the Net, but what exactly is it?"

Before Mac could answer, Dave interjected, "Inflation is when prices go up, hyperinflation is when they go up beyond all reason."

"But how do you know when you've gone from inflation to hyperinflation?" I asked.

"There's no hard and fast rule," Mac said, "and no exact number for determining when we've gone from one to the other—or bad to worse. But it's been said that inflation is reported annually while hyperinflation is reported more often, like monthly, weekly, or, in extreme cases, daily. It's not a bad rule of thumb. But let me make a quick comment about what Dave just said.

"It may sound like I'm nitpicking," he said to Dave, "but I'm not. Inflation isn't so much that prices go up—because that would imply that groceries and stuff like that have somehow become more valuable. Inflation is when money becomes less valuable so it takes more money to buy a sack of potatoes, a gallon of gas, or hire a babysitter. It's a distinction most people don't seem to get.

"In fact, in cases where commodities become more valuable, it's usually a case of supply and demand. When there's increased demand for something, or the supply of something we typically use runs short, the price of it goes up. For example, if a bad winter wipes out much of the citrus crop, oranges become more expensive that year. When the crop returns to normal, the next year, the price of oranges returns to where it usually is.

"Inflation, on the other hand, is an increase in the money supply that exceeds the expansion of the goods and services available to buy."

"That sentence sounds like a mouthful," I said. "Give me an example I can actually understand."

"Let's use an analogy," he said. "Imagine a bunch of us are stranded on a desert island with a set of poker chips. Our first year there, we decide the poker chips are going to represent the total of goods and services on the island because we want to use them as money. Say some of us harvest coconuts and we decide each coconut should cost five white chips. Next year there's a bumper harvest of coconuts. If there are too many coconuts, each one is going to be worth less than they were in the previous year because the people harvesting them are going to have a harder time dumping them all, so the price may fall to three white chips apiece to encourage people to buy them. On the other hand, if there's a bad harvest, it's going to be harder to buy them, so if consumers want them they're going to be willing to pay more for them and the price will go up. Maybe they're going to be seven or eight white chips each. But we expect the cost of a coconut to hover around the average price of five white chips we pay for them in a normal year."

"What you're saying is the cost of coconuts depends on supply and demand, surpluses and shortages," Dave said.

Mac nodded.

"I can see that," I said in agreement.

"Now," Mac continued, "let's take the same island and a raft drifts in with another set of poker chips that's the same as the first set. So, we effectively double the money supply on the island. What happens to the value of everything?"

I thought a second. "Well, if we accept the second set of chips as part of our money supply, with no increase or decrease in the number of coconuts, the cost of each coconut is going to be doubled because there's now twice as much money—or poker chips—on the island."

"That's right. And think about this: Anyone who's been saving his poker chips for a rainy day is going to suddenly find his stash of chips have half the purchasing power they used to have. That's inflation: an increase in the chips or, more generally, in the money supply and a decrease in the value of each poker chip or dollar."

"So, as more chips are introduced, not only do prices go up, but it discourages saving," Dave said.

"That's correct," Mac said.

"Then tell me if this is right," I said. "If instead of more chips showing up, half the chips on the island suddenly fall into the ocean and are lost for good, each remaining chip would now have twice the purchasing power they previously had and coconuts would cost half as much, because we said the number of chips represent the value of all the goods and services on the island, including the coconuts. That's deflation; a decrease in the money supply makes each chip more valuable."

"You've got it," Mac said. "By the way, a recent real-world example of prices going up due to supply and demand, and not inflation, was caused by a mandate created by Congress a few years ago. It stipulated that a certain amount of our energy had to come from ethanol. To comply with this mandate, fuel producers started buying a large portion of the grain harvests to make fuel. That took grains out of the market and created a shortage of grains available for human and animal consumption. The result was an increased demand on them without a commensurate increase in supply and we wound up with five-dollar loaves of bread as well as more expensive chicken, milk, and steak because it also cost more to feed the animals those grains."

"So that jump in grain prices at that time had nothing to do with the money supply, but with how much grain was available to make fuel," I concluded.

"Right again, and later on the cost of grain went down based strictly on market forces. But a lot of people labeled the price jump inflation when it wasn't."

"What should it have been called?" I asked.

"There is no convenient word or words in our language to cover the rise and fall of prices based on supply and demand, so we use the word 'inflation' indiscriminantly."

"Has this country always had inflation?" I asked.

"This may surprise you, but we've only had long-term inflation since the Federal Reserve was established in 1913 and they got control of our money supply. They have steadily increased the money supply faster than than the increase in the amount of goods and services that that money will buy. The result is that money has become worth less and less until, today, a dollar has about the same purchasing power as four cents had in 1913."

"Are you kidding?" I asked.

"No," Mac replied.

"But that means that a penny in 1913 had the same buying power as a quarter, today."

He nodded.

"What about before that?" Dave asked.

"Prior to the Federal Reserve, our currency had an amazing amount of stability for more than 100 years because it was based on gold. That is, prices remained pretty steady for over a century. The only thing that really happened is that prices went down as one technological advance after another made life easier, crops more plentiful, and businesses more efficient. There was a blip of inflation during the Revolutionary and Civil Wars, but those passed when those wars ended."

"People like Congressman Ron Paul want to go back to the gold standard," I said. "Why's gold so special?"

"Because it's rare, pretty, and useful, and we've agreed it's valuable," Mac said. "All the gold ever mined in the world would form a cube that was only 50 feet on each side. So there's a limited supply and if money was based on it, currencies couldn't help but be stable."

"But consider this," he added. "If someone suddenly found a pile of gold as big as Mount Everest, the price of gold would plunge until it was all but worthless because it wouldn't be rare anymore, though it would still be pretty and useful."

"I don't mean to cut you off," I said, "but why do we inflate our money?"

"Oh, there are economic theories that say it's good, but basically we do it because governments like inflation."

I was surprised. "Why?"

"Governments like to tax us and inflation is a tax. Most people simply do not understand that."

"How's it a tax?" I asked.

"Let's go back to the analogy of the island. As I said, if a second set of poker chips arrives, as they're introduced into the island's economy, the prices of everything on the island will begin to rise to reflect the number of chips. But before they do, the person who found the chips gets to spend them while the prices are still low. In effect, they're stealing the value out of everyone else's chips.

"In the same way, when the government increases the money supply, without a corresponding increase in the amount of goods and services, they devalue everyone else's dollars—they're worth less and buy less as prices begin to go up. But government gets full value with this newly created money because they spend it first."

"So, with inflation, they're stealing value out of every bill I have in my pocket," Dave said,

"Stealing is exactly what they're doing. Keep in mind that if introducing more money were harmless, the government wouldn't care about counterfeiters."

"So inflation amounts to legalized counterfeiting," Dave concluded and the three of us laughed at what he'd said.

"You're catching on," Mac said.

This concept clearly intrigued Dave.

"What's worse," Mac continued, "is that the same people who would scream at a tax hike or a new tax imposed on us, blithely ignore inflation because they don't understand that it's caused by the government and it's another tax. It's the ultimate withholding tax because it comes out of everyone's pocket even if you're in the underground economy. But the worst thing is that it discourages saving and investment, the things that made this country great."

"But it would still seem prudent to save even in an inflationary economy, wouldn't it?" I asked.

"We should try to invest our money somehow," Mac said. "But consider the effect inflation has on some types of savings, say a savings account, a certificate of deposit, or a U.S. Savings Bond. The interest paid on any of these is low. In fact, they're often lower than the rate of inflation. On that basis, the more you save the further you fall behind in purchasing power. But what makes it worse is that the interest paid is also taxed, that is, part of the imaginary gains you've made are taken away from you by the IRS. So, saving that way becomes a loser's game. The more you save, the further you fall behind.

"Over the long run, even putting money into precious metals is a loser's game—that is, if you do it honestly."

"How's that so?" Dave asked.

"If you invest in gold or silver, it's a nonproductive investment; it doesn't even earn you interest. What gold and silver really do is respond to the value of the dollar and other currencies. The price of those metals will go up with the inflation rate so, over the long run, if you hold onto them you should theoretically break even in purchasing power. The problem is that when you sell your gold or silver the IRS sees your gain as a 'real' gain and takes a chunk of it by taxing you. Thus, even precious metals are a losing position—unless you don't report the sale."

"So you're against holding gold or silver," I said.

"Oh, no. As a hedge against inflation they're terrific, but they're not making you money in the way stocks, bonds, or savings accounts would in a stable and noninflationary economy."

Hyperinflation in the past

"Other countries have already experienced periods of hyperinflation," Dave said. "The result of Germany having to pay war reparations after World War I led to that country's hyperinflation, and the hyperinflation led to Hitler's rise to power."

"The war reparations certainly contributed to Germany's inflation," Mac said.

"Were they intentionally inflating it to pay the war debt off with cheaper money?" I asked.

"No. Part of the Armistice agreement said the reparations had to be paid in gold or another stable currency, not the German mark. So inflating their currency didn't help them pay off the reparations at all. But paying the reparations did create part of the shortfall the German government had in its budget so they tried to make it up by letting the presses at the mint run, and it destroyed the German currency.

"However, hyperinflation alone wasn't the reason Hitler came to power. His ascendency was sort of a political perfect storm made up of the convergence of several important events, none of which, alone, was likely to produce a dictator. There was Germany's losing World War I coupled with the terms of surrender, the hyperinflation, the Great Depression, and other factors. There are those who want to say hyperinflation in this country could result in a Hitler of our own. But, again, it would take more than one event to make us that crazy. Not that it couldn't happen, but it won't just because of hyperinflation.

"Besides, Germany's hyperinflation was only one of several hyperinflationary periods that happened in many countries around the world during the 20th century, and none of those others led to the rise of another Hitler."

"How bad was Germany's inflation?" I asked.

"The German mark started losing value so fast that people were getting paid two and three times a day and they'd leave work each time so they could spend it before it lost even more value. They'd buy anything: Food, hard goods, knickknacks, who cared? If you didn't spend it right away, it was going to be worth a lot less in just a few hours. It got so bad that people not only spent their money as fast as they could, they often didn't bother taking their change."

"You're kidding," I said.

"You know how stores today have those little penny trays on the counter near the cash registers? 'Take one; leave one?' You buy something for a dollar ninety-nine and give the clerk a two dollars. He gives you one penny change and you drop it in the tray because a penny is close to worthless, nowadays. Suppose in a hyperinflationary period the price of a loaf of bread goes up to $19,900, something not at all inconceivable, and you've given the clerk two $10,000 bills. He gives you back a hundred dollar bill. That hundred dollar bill now has the purchasing power the penny used to have. It's easy to leave it on the counter and leave, especially because in a few hours it'll be worth even less."

"I know what you're saying is true," I said, "But I'm having a hard time wrapping my head around it."

"In October of 1923," Mac said, "prices in Germany went up over 40 percent a day. Money was so worthless you couldn't buy heating fuel with it, so to keep warm many people took to burning the paper bills instead."

"Wow!" I said. "Can it get worse than that?"

"Believe it or not in Hungary, just after World War II, the Hungarian pengö lost its value even faster. Throughout July of 1946, prices tripled everyday. What cost 1000 pengö one morning cost 3000 the next and 9000 the morning after that."

"People must have been outraged," I said.

"I agree, but the circumstances also honed their senses of humor."

"Is this a joke?" Dave asked.

Mac kind of smiled. "There are stories about incidents during hyperinflationary periods that may or may not be apocryphal, but they give you a good idea of how people can find humor even in dire situations.

"The first one involves a man in Germany, during the post World War I hyperinflationary period of the Weimar Republic. He is said to have paid his fare upon boarding a bus. When he reached his destination, he was informed he'd have to pay more to get off the bus because the fares had gone up during the trip."

"Can they do that?" I asked.

"Who knows?" Mac replied and he looked at me as if I was crazy for asking. "Like I said, I don't even know if it's true, but it reflects how people felt about the rapidity with which their currency was being devalued."

"It sounds like the old Kingston Trio song, Charlie on the MTA," Dave said. "Charlie couldn't get off the trolley because the fare had gone up a nickel and he didn't have one on him." Both Mac and I thought that was funny because we're familiar with the song.

"Another story...and keep in mind, John, these may not be true...involved a student in Hungary who went into a coffee shop during their hyperinflationary period and ordered a cup of coffee. After he finished it, he ordered another cup. When he went to pay the bill, it was for more than he'd expected. When he complained, he was told he should have ordered both cups at the same time because, while he was finishing his first cup, the price went up on the second one."

Dave glanced at me as if expecting me to ask, "Can they do that?" again. But I'd learned my lesson.

"But to me," Mac said, "the funniest story is about a man in Germany in 1923. This one may be true. He put his money in a wheelbarrow and headed off to the store to buy a loaf of bread."

"All he was going to get for a wheelbarrow full of money was one loaf of bread?" I asked.

"Listen to the story," Dave said.

"Yes," Mac said. "It got so it took a wheelbarrow of money to buy a loaf of bread. But when he got there, the store was closed. He left his wheelbarrow outside the door, figuring he'd come back when the store opened, knowing the bundles of money in it weren't worth enough for anyone to steal. And he was right. When he came back, the money was still there, dumped on the ground, but someone had stolen his wheelbarrow."

That story was funny in a perverse kind of way, so funny that, for some inexplicable reason, I wanted to believe it was true, but I didn't say anything.

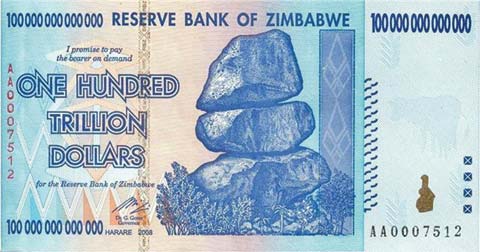

Zimbabwe hyperinflation

Mac continued, getting back to actual historical accounts. "Today, Zimbabwe is undergoing hyperinflation. Their hyperinflation started when the country's president, Robert Mugabe, took land away from the former white landowners to give to blacks who, unfortunately, were unfamiliar with agricultural practices. Crops failed and Zimbabwe began having problems feeding itself. As a result, food prices jumped and Mugabe started to run the presses to keep up with the price increases. Coupled with that was his decision to quadruple the pay of the police and the military, without putting it in the budget, and the presses had to run even faster and longer to make up for these and other budget shortfalls."

"I'm guessing he increased their pay to keep their allegiances," Dave said.

"That's my guess, too," Mac responded. "Of course, each jump in inflation sent all prices further skyrocketing and the presses were run to keep up with that, so prices climbed even higher..." He raised his arms as if he were lifting the prices himself.

"It becomes a vicious circle," Dave said. "Prices go up, so you print more money so the government can make purchases, but that makes prices go even higher, and so on."

Mac nodded. "There was a time when the Zimbabwean dollar was worth more than the American dollar. Today, it's possible to find 100 trillion dollar Zimbabwean notes, but no one wants them. You can't even bribe a Zimbabwean official with Zibabwean money."

"A 100 trillion dollar note? I'd love one," I said dreamily. "I'd be a trillionaire."

It may have been because of the wine, but they both laughed.

"Yeah, imagine the girls that would want you then, John," Dave said. "I'm going to get you one of those bills."

"Many South American countries," Mac went on, "Argentina, Brazil, and Bolivia among them, experienced hyperinflation in the late part of the 20th century. All of it was the result of government overspending; when the bills came due, unable to pay them with taxes, the respective governments ran the printing presses and got caught in that same vicious circle."

"Do you think it could happen here?" I said thinking back to the comment I thought I'd heard him make as I was coming into the building—that we may be headed for hyperinflation.

He thought about my question. Then, he said, "In the past, common causes of hyperinflation have been war, when governments couldn't raise money fast enough through taxes or the sale of bonds to pay to keep its war machine running. But, that's changed. As you can infer from the examples I gave, nowadays, whenever governments have accumulated extreme debts that they are unable or unwilling to raise the money to pay off, either with the sale of bonds or the raising of taxes, they often resort to simply printing more money by running the presses, whether it's the paper presses or the virtual electronic presses of the computer age that create electronic credits.

"Governments have streams of commitments, and more often than not they're political promises politicians make to voters to keep themselves in power. And for them it's often only about staying in power. But, having made those promises, they often can't renege, even if there's no money in the treasury to keep them."

"Such as what happened to Mugabe in Zimbabwe," Dave said.

"So they order the presses to run and print money, oodles of money, to pay the bills. That's what happened in Germany, Hungary, Zimbabwe, and, in last third of the 20th century, several South American countries. They all experienced runaway inflation because they borrowed too much and couldn't pay off the debts, and they continued their high-spending practices.

"Do you see where this is going?" he asked.

"Their solutions were to let the presses at the mint roll," Dave said. "So, neither inflation nor hyperinflation can exist without the government having a hand in it," Dave said. And before Mac could answer, he added, "In fact, from what you're saying, government is the cause of both inflation and hyperinflation."

"Ah. If only the American electorate could understand that, we'd throw all the bastards currently in Washington, DC, out and get officials who care about this country. Well, throw out all but Ron Paul, of Texas, who is the only one there who both knows and cares about what's going on."

Neither Dave nor I said anything. We both know of Mac's respect for Paul.

"At some point, the politicians may try to blame it on the 'greedy bankers,' speculators, and black marketeers, but none of them can run the presses," Mac added.

"What ends hyperinflation?" Dave asked.

"First, they've got to stop creating money out of thin air. Second, a new currency has to be established. Generally, issuing a currency backed by something tangible, like gold, will prevent the inflation of the currency in the future. Third, the government has got to get its spending under control. A balanced budget is the way to do it."

"What about the Federal Reserve?" Dave asked. "That's not a part of our government, but it manages our money. Are they doing a good job?"

"The Fed may as well be part of the government because Congress could dissolve it tomorrow, if it so wished. And is it doing a good job? As I said before, the dollar now has the purchasing power four cents had when they started out.

"But let's get back to whether hyperinflation could happen here. Consider our unfunded debts. These include the costs of Social Security, Medicare, national healthcare, the trade deficit, and the bailouts—for which trillions were manufactured out of thin air in a way a Zimbabwean strongman could only dream. We owe trillions in loans to foreign governments, most notably China. The responsibility for paying all of this off is being thrown on the backs of the young and those yet unborn.

"There's no way we can keep this up. In fact, when the younger generations of voters come of age and they realize what we and the other older generations of voters have voted ourselves, and that we've saddled them with the onerous task of trying to pay off these unpayable debts, they may just welcome hyperinflation and screw us the way we've been screwing them, for example, by making our savings and Social Security payments worthless.

"But not only do we have all this debt, a lot of our currency is overseas. Foreigners have been willing to hold American dollars for decades because it's been universally recognized and it's been considered stable. But, if all those dollars were to come back here and were spent in a short time, it too might lead to hyperinflation."

"It would be like the raft with a duplicate set of poker chips suddenly showing up on the island," Dave said.

"That's right."

"You mentioned Social Security," I said. "But in the beginning, Social Security was a good idea and it was self-sustaining. Right?"

"Actually, it was never self-sustaining. If any insurance company were to set up such a plan, the stock holders would revolt and the government would throw the officers in jail. In fact, in the early 1950s, several insurance companies approached Congress and showed them that Social Security, the way it was conceived, was unsustainable and offered to manage the system and turn it into something other than the Ponzi scheme that it is. You know what a Ponzi scheme is, don't you?"

Dave said, "It's a financial scheme where the people getting in early are paid off with money put up by later ones, rather than from some kind of profits, in order to encourage more people to come in and take bigger risks. And it falls apart when too many people want their money back and it's shown to be insolvent."

Mac seemed to be surprised Dave knew this. I know I was.

"At the beginning," Mac said, "when Social Security was set up, there weren't many people collecting, so the millions and millions of contributors had no problem supporting them, and only a little came out of each person's paycheck to keep it going. But, as the number of people collecting increased, and as Congress kept voting bigger slices for those who were collecting, those getting in later had to give up a bigger portion of their paychecks to support them.

"In the future it's going to reach a point where the amount taken out of workers' checks is going to be horrific and, ultimately, the system will start running in the negative. Young people coming into the workforce will be forced to pay huge amounts of their incomes to keep it going, with no chance of collecting anything meaningful when it comes their time to retire. Long before that point, I wouldn't blame them for revolting and it will be these younger generations that may welcome hyperinflation to pay the debt off."

"It sounds like we're bankrupting our country," Dave said, "and if we don't stop, the only way out of it may well be to let hyperinflation happen."

"But what happens if we do that?" I asked.

"There will be winners and losers," Mac said. "The prime winners may be future generations, including those not yet born, with whom we've been trying to saddle all these debts. You must keep in mind that the last few generations, including our own, have been the most selfish in American history. We've voted ourselves all kinds of benefits that are going to have to be paid by the young. But there's going to come a time when the young realize it. We can't hide it forever. And when they see what's happened, they're going to do something about it at the polls. As a result, it's likely to be the older people who are going to be hurt."

"Including our generation," Dave said.

"In almost every country where inflation has gotten out of control, many who had spent their lives providing for themselves with investments and savings found the purchasing power of their retirement nest eggs wiped out by the hyperinflation, the value of their savings stolen by a government. And those who watched their retirement disappear overnight had to return to the workforce in their old age."

"But won't young people be hurt, too?" I asked.

"The young are resilient and have their whole lives ahead of them. They may be better off if hyperinflation manages to wipe out the debts we've been trying to saddle them with."

"I heard hyperinflation might help a lot of homeowners who are behind on their mortgages because it would allow them to pay their mortgages off with inflated dollars," I said.

"Keep in mind," Mac said, "that the recent bailouts went through despite polls showing the public was against them. It's because Wall Street and the bankers have Washington's ear. So, for better or worse, Congress is likely to step in and make laws saying mortgages and other loans, such as car loans and credit card balances, would be inflation-adjusted."

"That would be tantamount to another bailout," Dave said.

"Isn't there a way to keep prices down despite inflation?" I asked.

"You mean like wage and price controls?" he asked.

"Yeah."

"They don't work. At best they do nothing, at worst they destroy businesses and jobs. By instituting wage and price controls, policy makers force sellers, under penalty of law, to sell their goods and services for money that is worth less and less every day. They force workers to work for less and less of a living wage. The result is that sellers may wind up selling goods at a loss and may go out of business while workers struggle because they can't pay their bills. So we have scarcity of goods, lost jobs, and a burgeoning black market. Even if the prices stay down temporarily while the controls are in place and the government threatens penalties, once the controls are lifted, the prices shoot up to where they should be. If you'll recall, this is what happened when Nixon tried to impose price controls in the early '70s.

"Price controls also force businesses to either withhold their products from the market or they force them to sell on the black market in order to survive. Goods including food and clothing often disappear from the shelves, and people walk away from their jobs to work under the table. Politicians are against black markets because they expose political policies for what they are—shams—and they can't tax them."

"What could we have done differently to have prevented this?" Dave asked.

"We could have voted differently."

"Voted differently?"

"It can't be that simple."

"It is. It's the Democrats and Republicans we've been voting for for the last several decades. They created the debts that may lead to hyperinflation, and the American electorate chose not to stop them and kept reelecting them year after year."

"How were we to know what was coming?" I asked.

"You should have turned off the sitcoms you watch, turned off the football games—just a few nights a year—and gotten yourself informed. The problem with the American electorate is that it doesn't want to inform itself of what's going on in the world, but it still wants the right to vote."

"I see what you're saying," Dave said. "Ultimately, we're responsible because we let it happen. Is there anything we can do now, before it happens?"

"Go back to the Gold Standard—it kept our money stable for over a century—and start paying our debts and stop expecting the as-yet-unborn to pay them for us."

"That's not likely to happen," Dave said. "Sooo..." and he paused, "What is O.E. MacDougal doing to protect himself?"

"Well, if we're lucky, we'll watch our currency inflate slowly and we can get rid of our dollars and turn them into hard assets. But I'm already hedging my bets. I buy hard assets, everything from junk silver coins and ammo for the guns I own to food and wine. I have lots of food, lots of wine. It's also good if you can get your hands on some stable foreign currencies like the euro. But, if not, the junk silver coins will be good, maybe better, because they'll be universally recognized as good currency because of their silver content."

"There was some gas station over in Medford, Oregon," I interrupted, "that was selling a gallon of gasoline for a quarter that was made prior to 1965. Those are the silver ones, right?"

"Yes, and we may see a lot more of that in the future," Mac said. "Especially if inflation is running rampant. You'll be able to buy a bag full of groceries for a few silver dimes while people are getting a mere loaf of bread for a thousand inflated dollars. Then you'll get another bag of groceries, a few days later, for the same number of dimes, while the price of bread has gone to $2,000 in almost worthless currency."

"So, you think it will happen," I said.

Mac smiled. "Like I said earlier, no one can predict the future. But let me add, it's prudent to hedge your bets."

Back To Leeconomics.com